In an interview with Malaria No More, Dr. Photini Sinnis, the Deputy Director of the Malaria Institute at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, discusses her latest malaria research, as well as her outlook on what to expect in 2024 given the spread of the Anopheles stephensi species, climate change, last year’s reemergence of malaria in the United States, and other challenges.

What is your team currently working on?

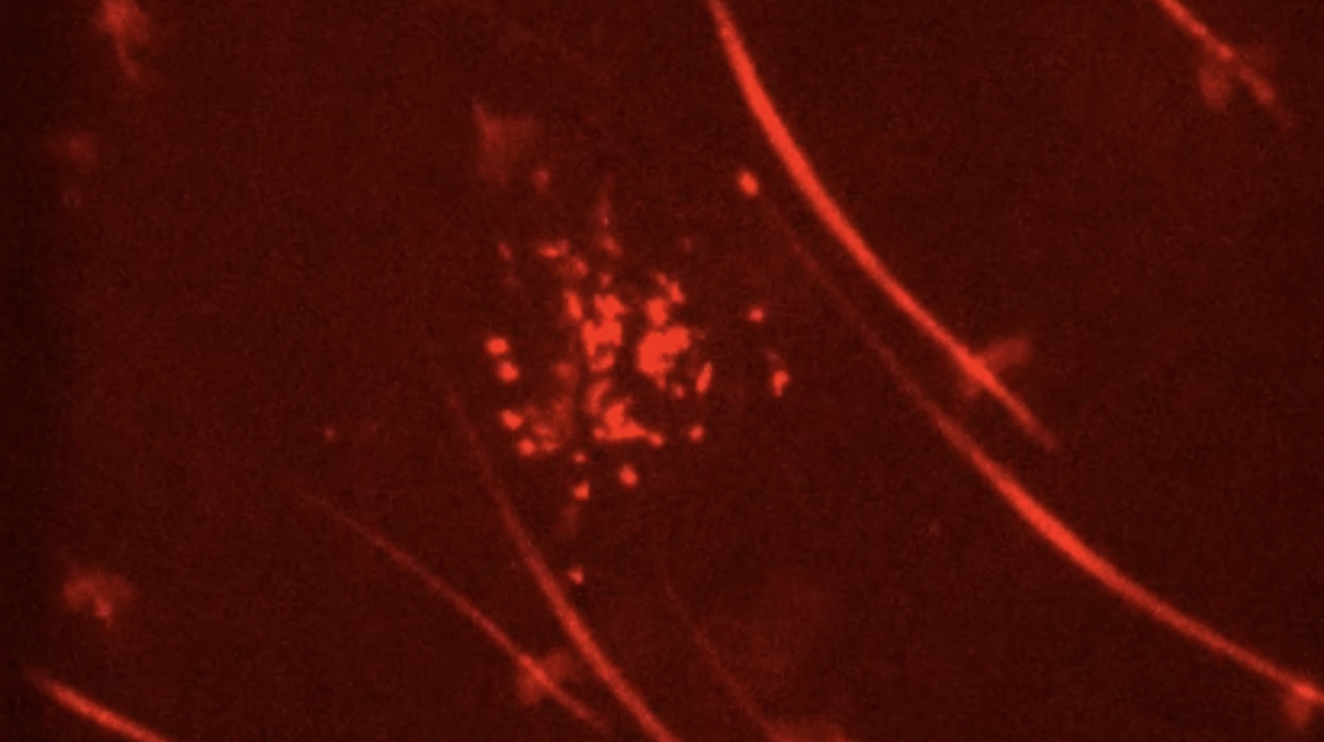

SINNIS: My team works on the sporozoite stage of the parasite, or when infection gets established. It's completely asymptomatic. You don't know you've been bitten by an infected mosquito until 7 to 30 days later when you have a blood stage infection, because the number of parasites at the sporozoite stage is low and increases exponentially in blood stage infection.

We also study the biology of sporozoites. We are interested in its major surface protein and how it functions, because the major surface protein of the sporozoite is the target of the two malaria vaccines that have been approved and have shown efficacy. We don’t know much about the protein and with a better understanding of the protein, we may be able to make the vaccine better by targeting different regions of the protein.

You recently co-authored a new report on the malaria parasite. What were the key takeaways?

SINNIS: This report was about how many parasites … are in the mosquito, and whether it's an important determinant of if a person gets infected.

For the last 30 years, it’s been thought that any infected mosquito is equally likely to initiate an infection in a person, and that how many parasites are in that mosquito, doesn't matter to transmission likelihood.

In that case, it would mean we need to get rid of almost all the infected mosquitoes to get rid of malaria transmission…

So, in this latest study, we asked the question: if a mosquito is more highly infected, does it inject more sporozoites. And we found a very strong correlation between how infected a mosquito was and how many sporozoites are injected.

How do those findings ultimately protect people from malaria?

SINNIS: The next step is to do the experiment in humans. Given we now know that more heavily infected mosquitoes are more likely to inject more sporozoites, the next question is, is that more likely to lead to a blood stage infection in humans? We are now trying to get funded to do a controlled human malaria infection.

So, these controlled human malaria infections are basically where you put infected mosquitoes on a human. You let them probe or bite. And then you can wait seven days for the sporozoites to go to the liver and develop in hepatocytes then seed the blood. We can take blood from people starting on day 5 or 6 and start seeing parasites if they're going to become infected and treat them.

This model, which is incredibly safe, can then be used to test vaccines and drugs. You vaccinate a group of volunteers, with an unvaccinated control group, and then you can expose everyone to infected mosquito bites and determine if the vaccine protected the vaccinated group.

The other way we can take it…we can try to trace genomes and sequence the genomes …to see if mosquitoes that high infections have are more likely to transmit. That’s more complicated, but really the question is, are there superspreading mosquitoes. Another way to put it is, are 20% of mosquitoes responsible for 80% of infection? It’s an important basic thing to know.

If heavily infected mosquitoes are primarily responsible for transmission, there are a few downstream impacts. One is, those working on preventing the mosquito from getting infected…and the benchmarks for transmission blocking interventions could change depending on our data …Because if [other researchers] don't have to get their interventions to block 100% of mosquitoes being infected, then many of the interventions that they've come up with are ready for testing in the field.

Such as getting rid of superspreaders?

SINNIS: Exactly. And we also can make better epidemiological models. Right now, our transmission models are on a very large scale, and we don't understand transmission on a very local level. And it may be that local level transmission can be better understood if we understand how many highly infected mosquitoes there are versus low.

If all infected mosquitoes are important to transmission, then we've got to treat everybody in sub-Saharan Africa. But if only highly infected mosquitoes are important, this group of people, mostly adults that have very low infections, we don't have to treat them in mass test and treat strategies. This has important downstream ramifications.

at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Are you concerned about climate change?

SINNIS: On many levels. I do think that malaria may come back to the temperate regions of the world, and we may see sporadic epidemics. Last summer, we had ten confirmed cases of local transmission.

We eliminated malaria transmission in the United States by 1959. And since then, we've had sporadic local transmission because the mosquitoes are still here. We have travelers, we have military, we have people from endemic countries coming. And if a mosquito bites them and lives long enough so that the parasite develops and then bites somebody else, we can see malaria in people who have never left the country. Right now, it's a low probability event, but it happens occasionally.

And if you look back on when it happened, it was usually very hot, humid summers …optimal conditions for mosquito survival. Nowadays, our summers are always hotter than the year before. Spring started last year in February or March, which gives mosquitoes a longer period to build up their populations…Come spring, numbers start going up. And if spring starts earlier, the numbers start going up earlier. So, your total population of mosquitoes can go up with these warming winters, increasing the probability of an encounter between an infected mosquito and a person.

The other thing that was interesting about 2023 was that in contrast to other locally transmitted cases since 1959, when it occurred in one or maximum two geographic locations, this summer it was in four independent geographic locations, which may be meaningful.

Both climate change and malaria transmission are complex, so you can't definitively attribute this to climate change. We have to wait and see what happens over time.

I think it's very possible that malaria may come back to the United States in sporadic epidemics that occur every year rather than once every five or ten years.

And…we know …very, very little about the Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit malaria in the United States…Only Anopheles mosquitoes transmit malaria…and we know nothing about them. What are their habitats? … what do they need for survival? How good are they at transmitting? How can we kill them? We know a lot about the mosquitoes in sub-Saharan Africa, and we just don't know much about the American Anopheles.

We are hoping to get some funding to study the American Anopheles mosquitoes. We don't know what the future holds in terms of malaria in the United States but at the very least, we should be prepared.

Looking ahead at 2024, are concerned about the impacts of El Nino?

SINNIS: I think we're all waiting to see … if we're going to continue to have locally transmitted malaria in the United States. These things happen slowly, so I would think local malaria could increase, but maybe it'll be about the same level as we saw last summer.

While nobody died, it is something we should be preparing for, because it’s here and possibly getting worse: Climate change is not going away.

How should we be preparing?

SINNIS: We need to learn about these mosquitoes. The current response to mosquito transmitted infections is to spray the area. It's a sledgehammer. It’s temporary. And, there are a lot of unintended consequences to mass spraying. So, why not use a scalpel? And we can't use a scalpel, rather than a sledgehammer right now, because we don't know where to cut.

The more we learn about these mosquitoes, the more tools we’ll have at our disposal. For example, if we know their habitats and where the adult female lays her eggs, maybe we can go to those habitats and put out larvicides. Much less dangerous for people, and more effective. I think that’s where we want to go - learning more.

###